From the Christian Aid website:

‘The 50th Christian Aid Book Sale takes place on 14, 16-20 May at St Andrew’s and St George’s West Church, George Street, Edinburgh.

Since it started in 1973 the sale has raised over £2m for Christian Aid’s work to end poverty.

During Christian Aid Week, over 500 volunteers from Edinburgh and beyond work together to create the UK’s biggest fundraising event.

Over 100,000 books of every kind fill the sanctuary and both courtyards. But there’s much more than books. Upstairs in the gallery you’ll find sheet music (and more books!). Downstairs in the Undercroft Café you’ll find delicious homebaking. In the Davidson Room, hidden, at the back of the church you’ll find a treasure trove of antiques and collectables. And did we mention the toys, records, stamps and postcards?’

***

Three years ago, Mon and I said that the Christian Aid Book Sale in Edinburgh was going to be our new yearly tradition – the following year was 2020. Need I say more? This year – the year of the 50th Book Sale, no less! – we finally returned, and were accompanied by the wonderful Ellis and Rosie (of Yorick Radio Productions fame). The weather was beautiful and sunny, the books were aplenty, and though I was stricter with myself than 2019 and only bought eight books – in contrast to 2019’s twenty – I still had a wonderful time. How could I not, browsing books with friends?

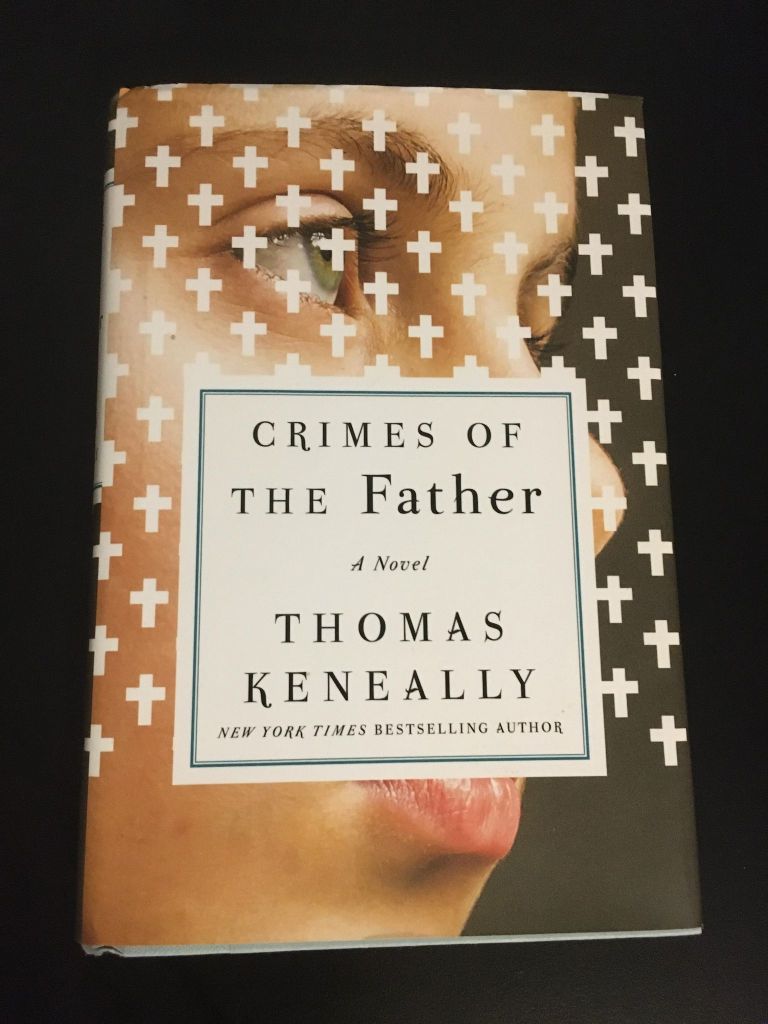

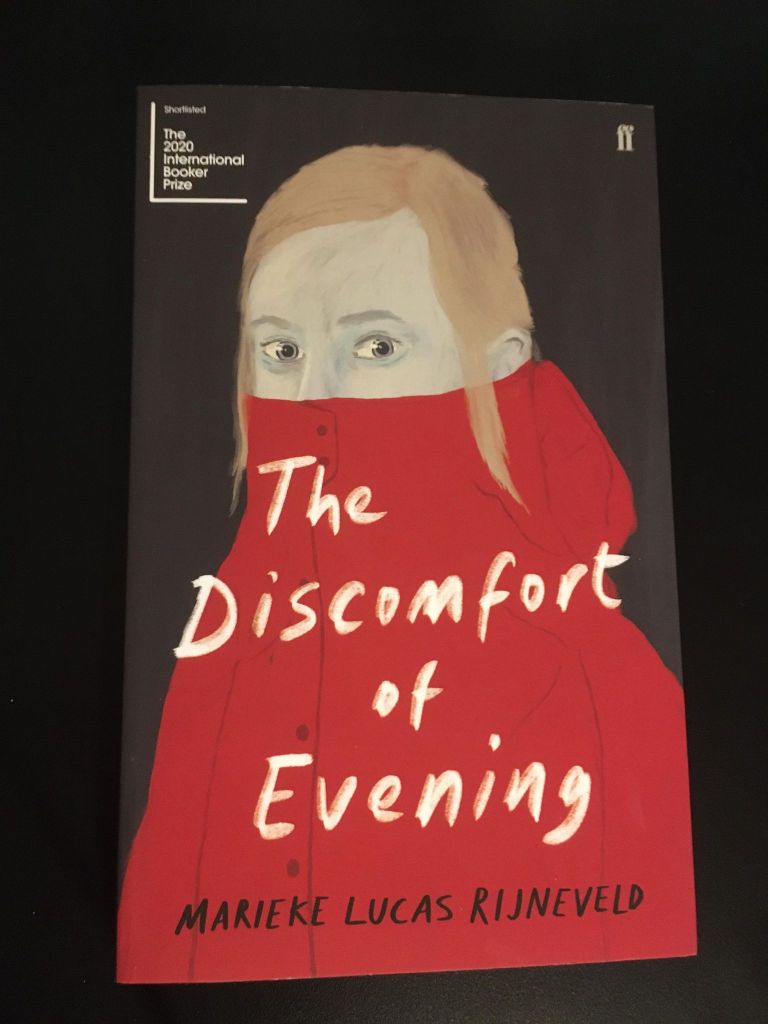

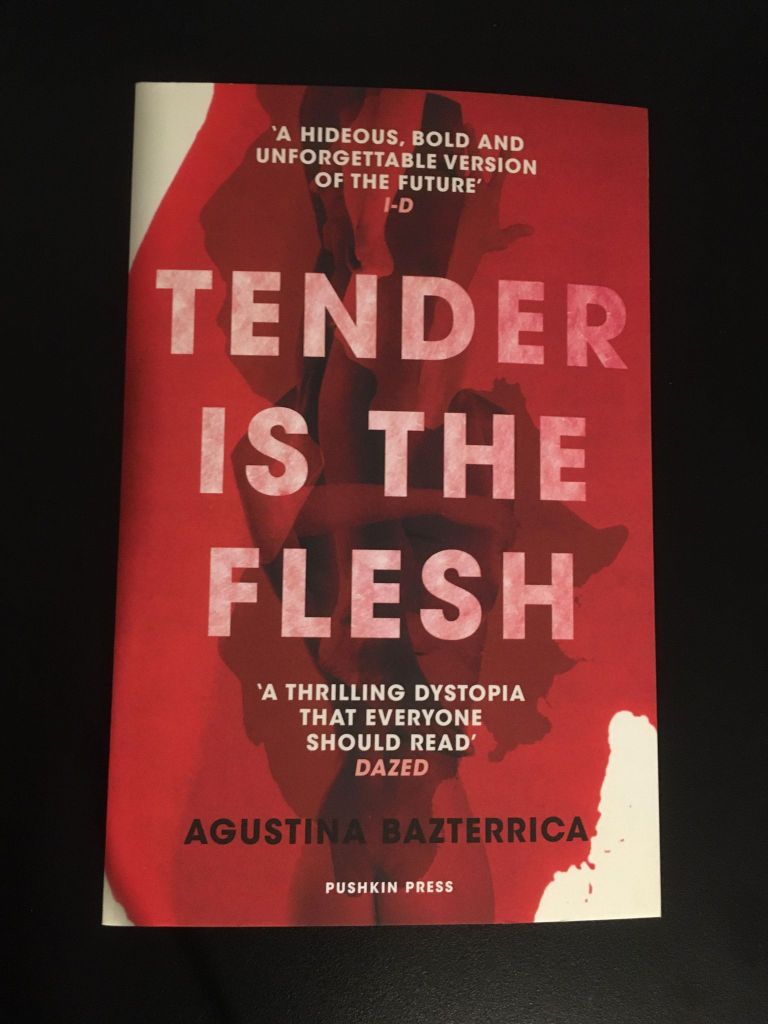

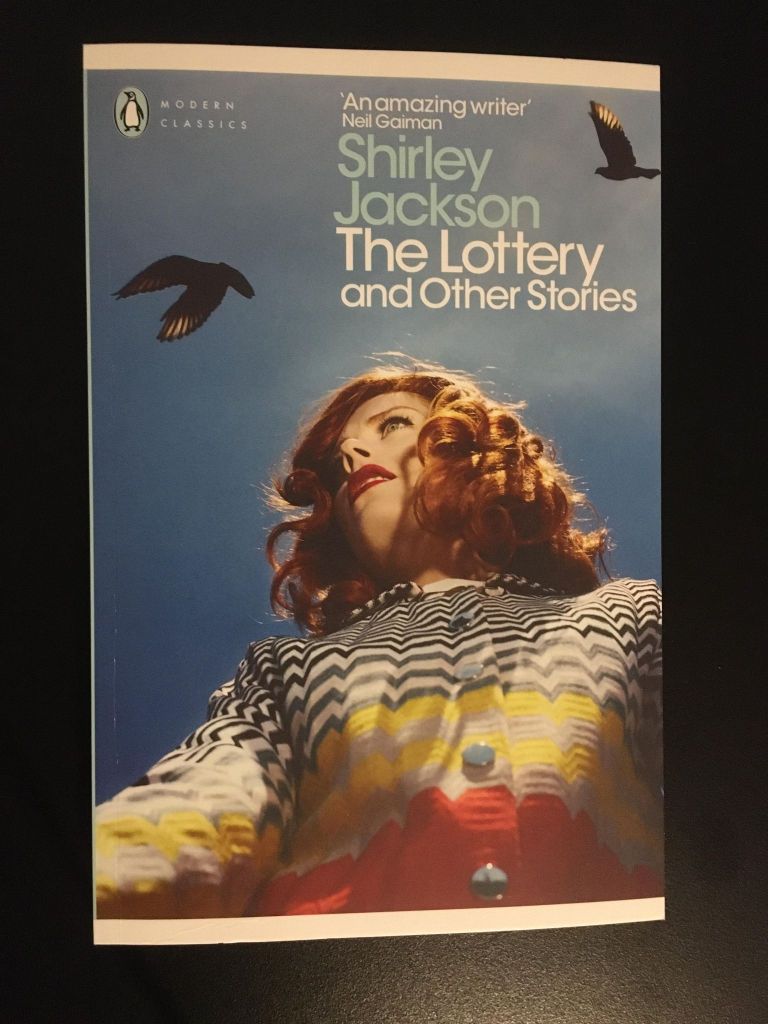

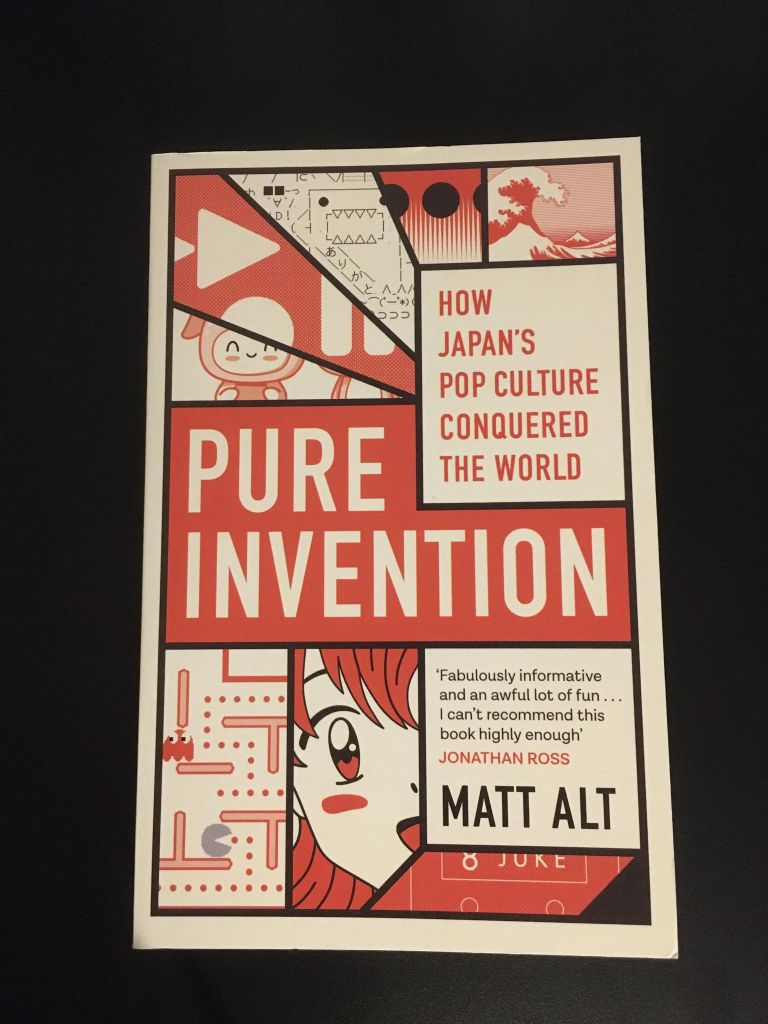

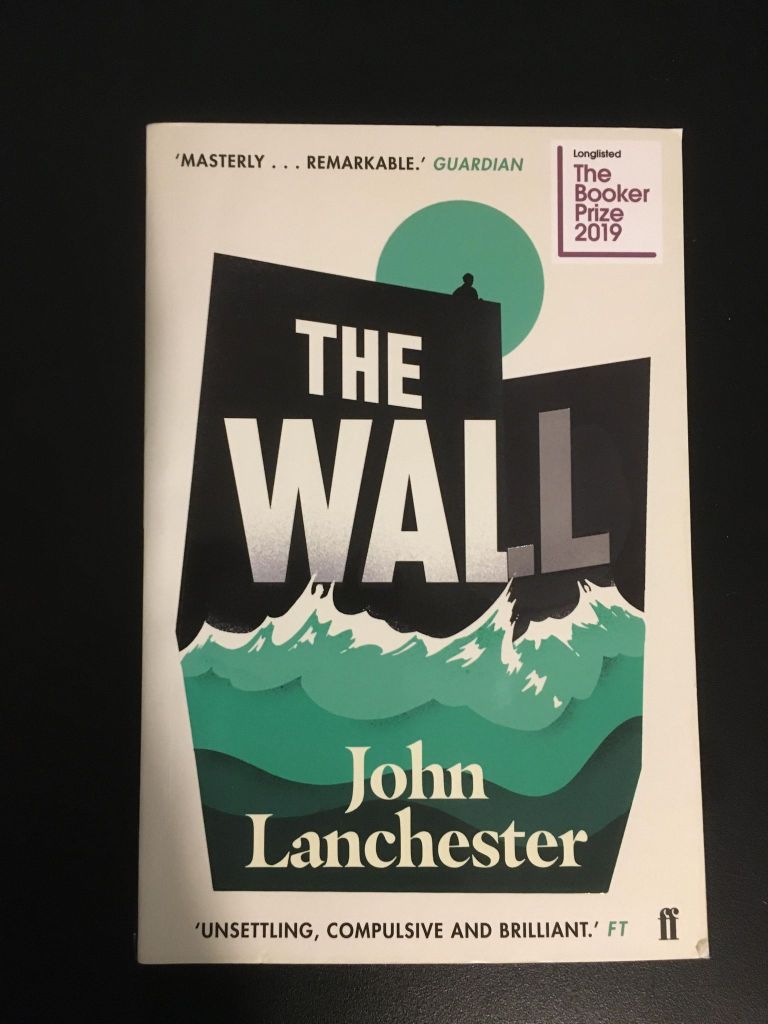

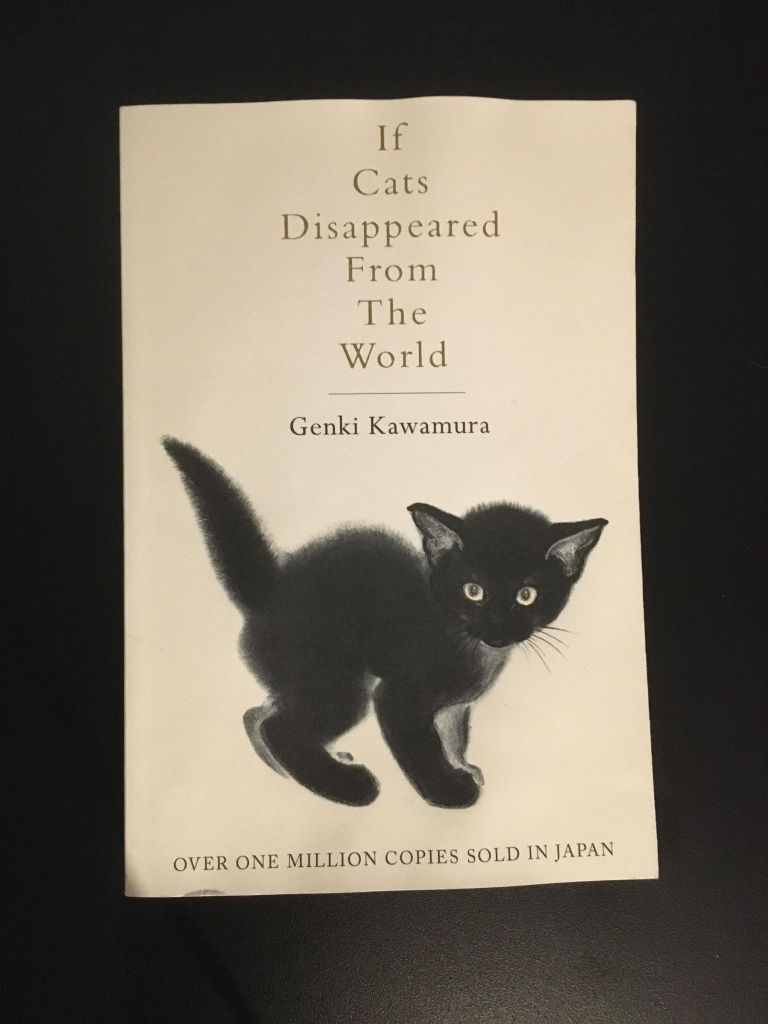

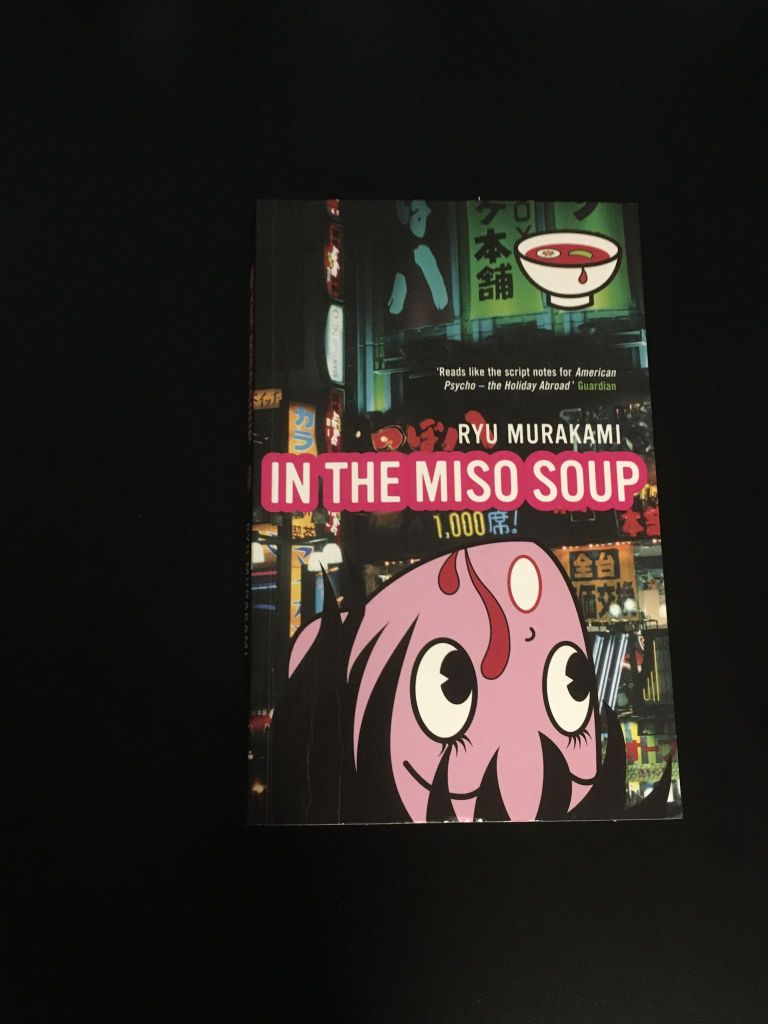

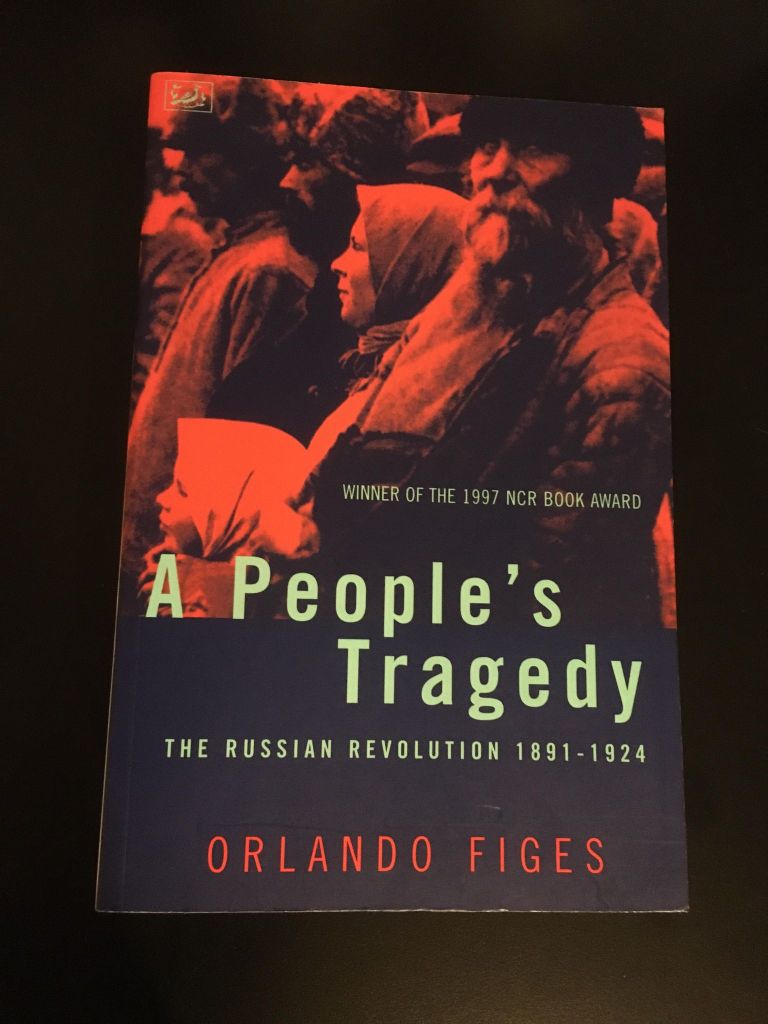

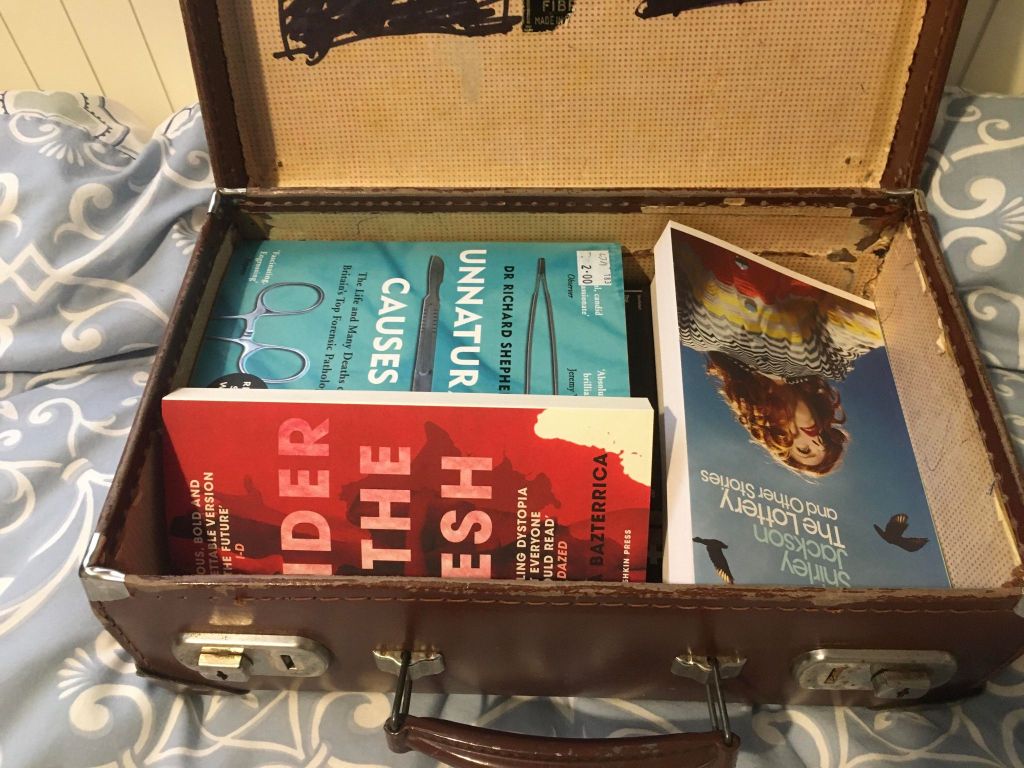

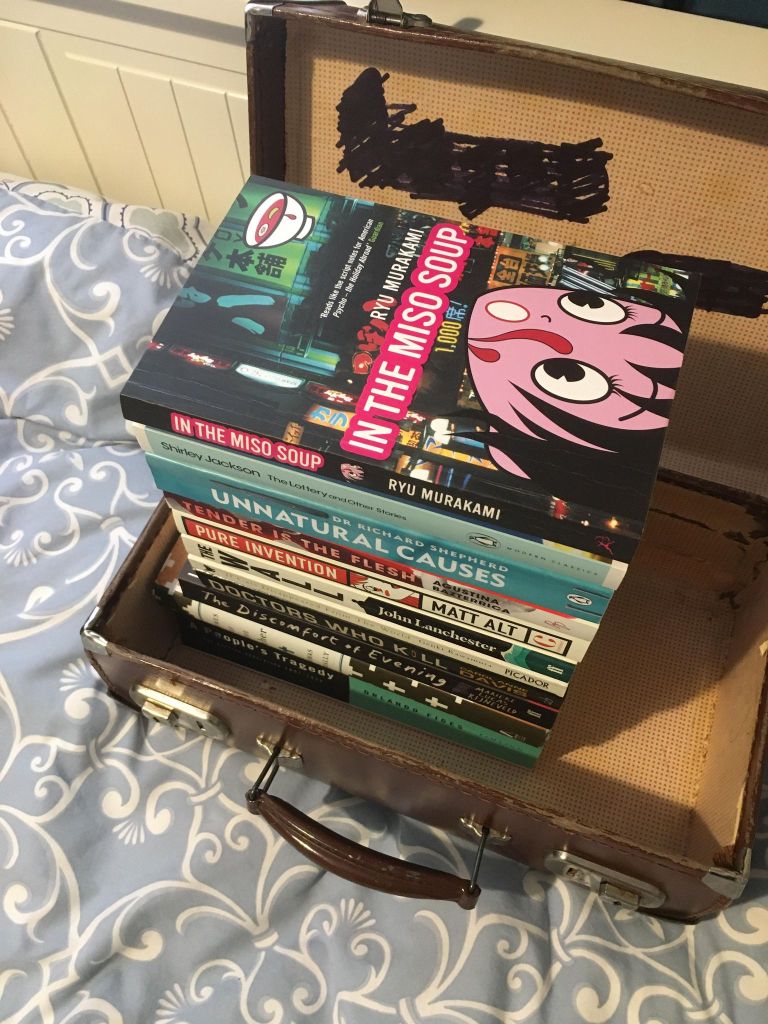

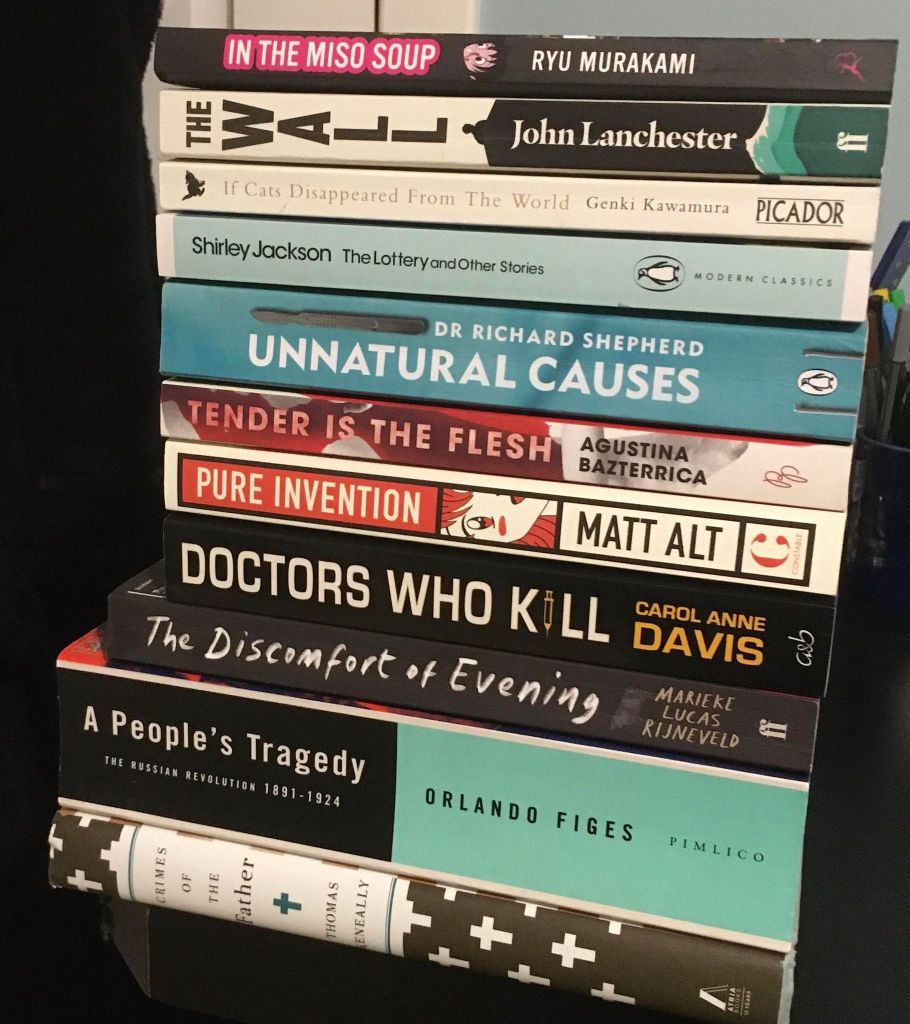

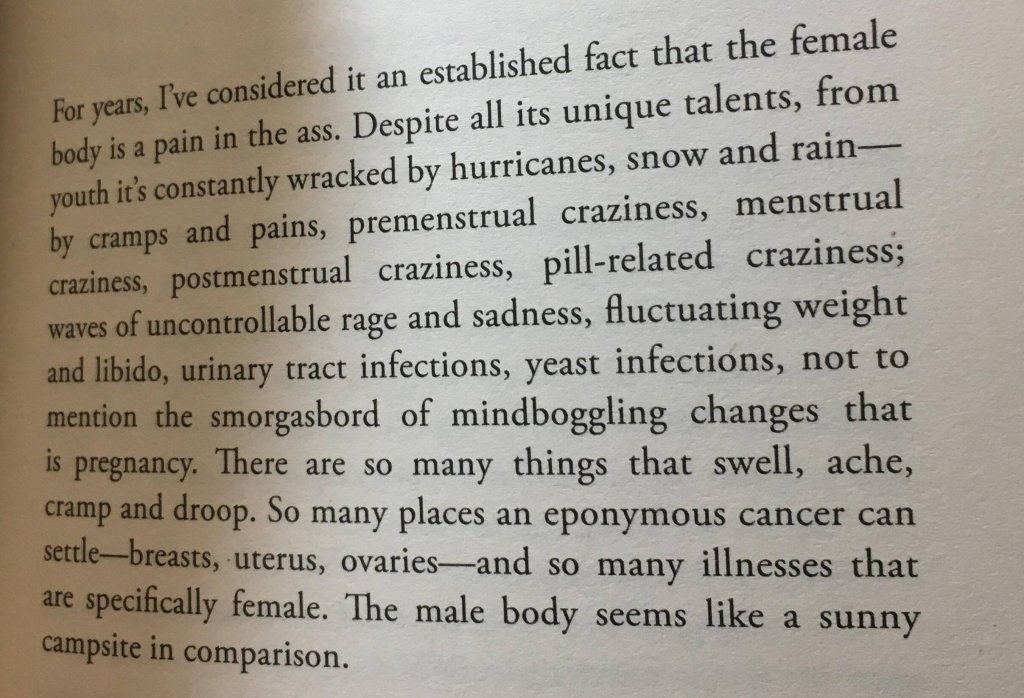

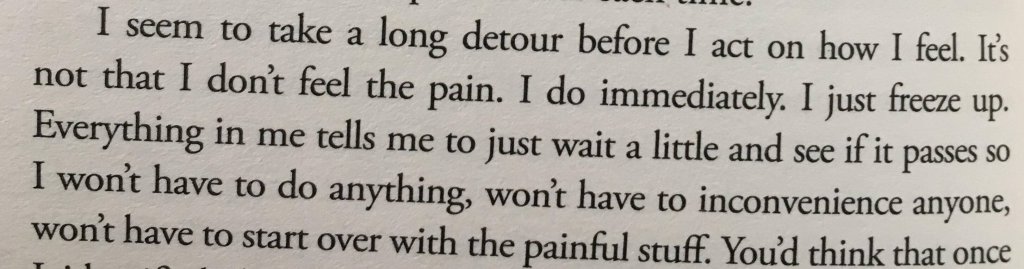

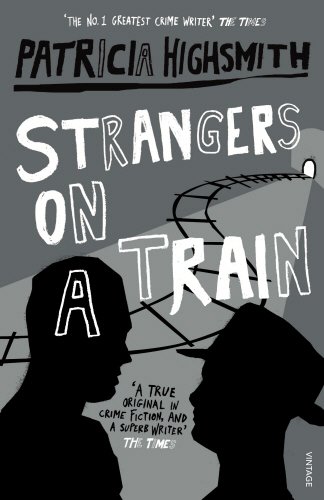

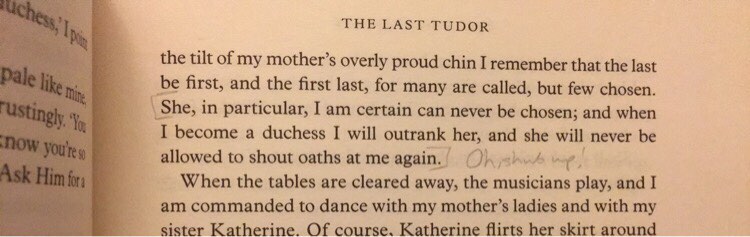

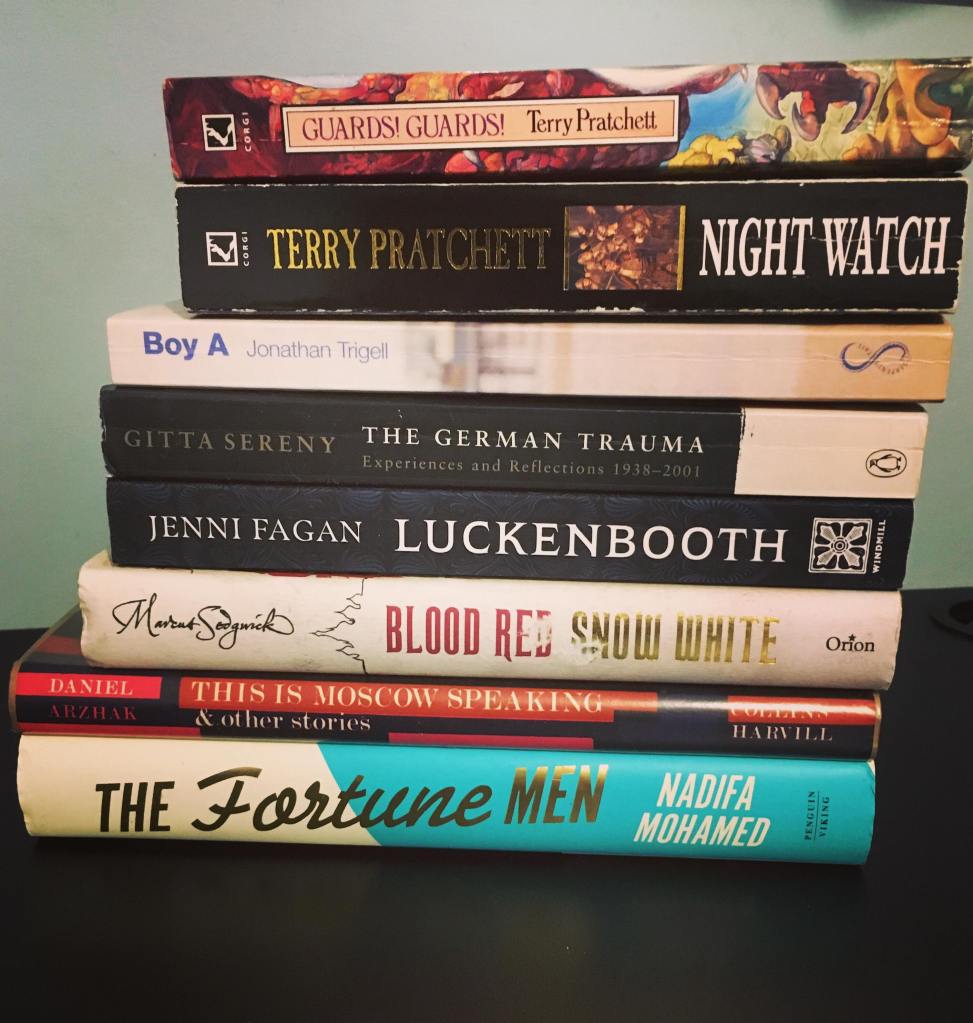

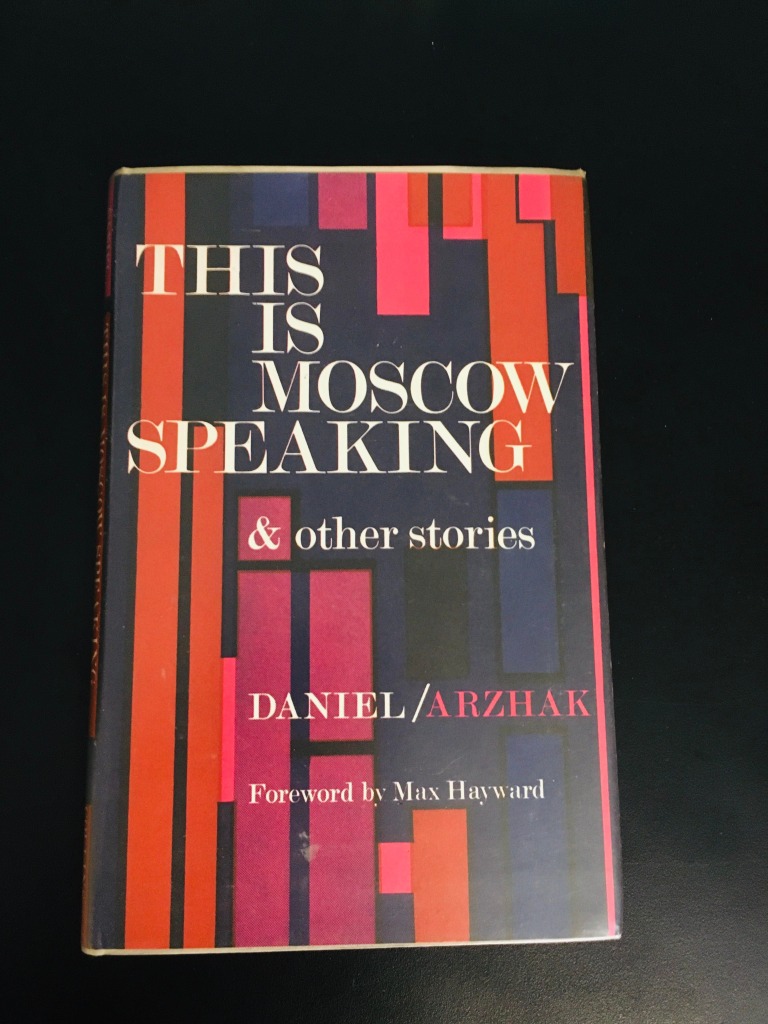

Obligatory book pile picture:

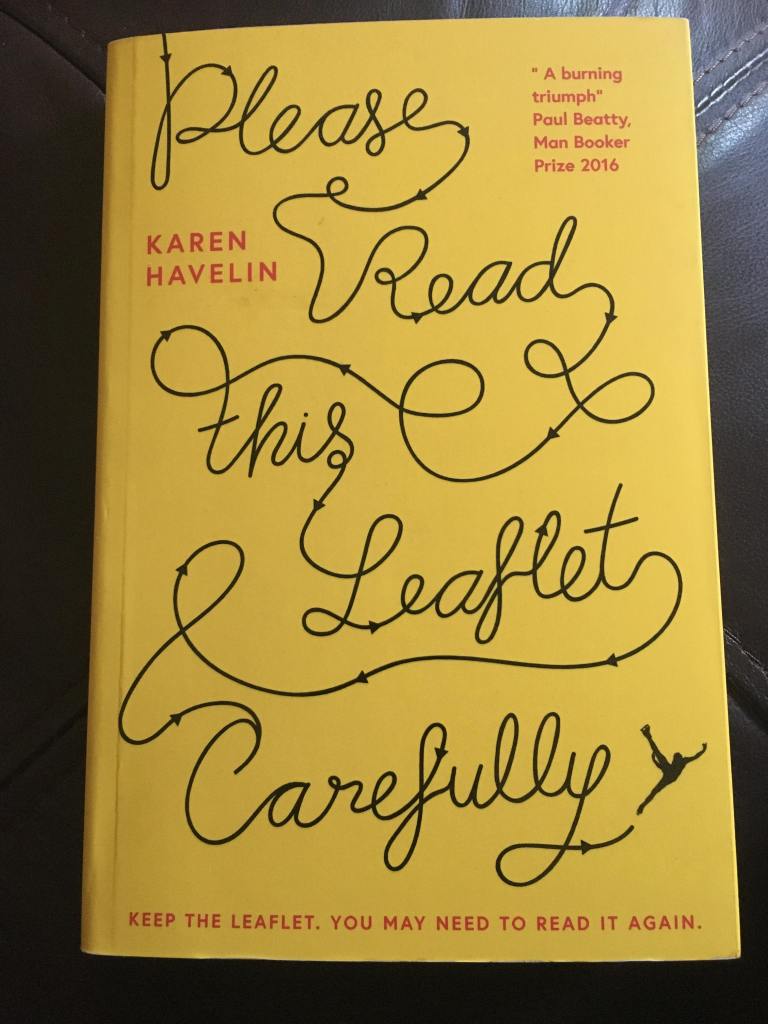

And now, the books in more detail – some nonfiction, some fantasy, the obligatory book on Russian history, and one book that was shortlisted for the Booker Prize in 2021! All blurbs are from Goodreads (even though I’m using The Storygraph these days, shh):

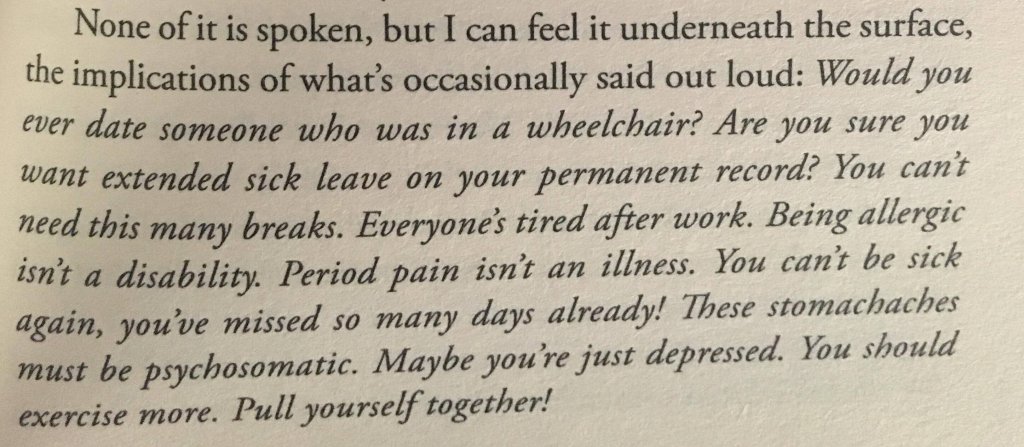

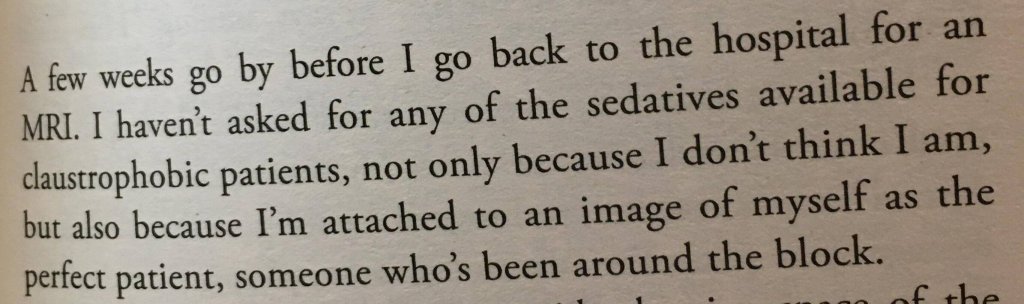

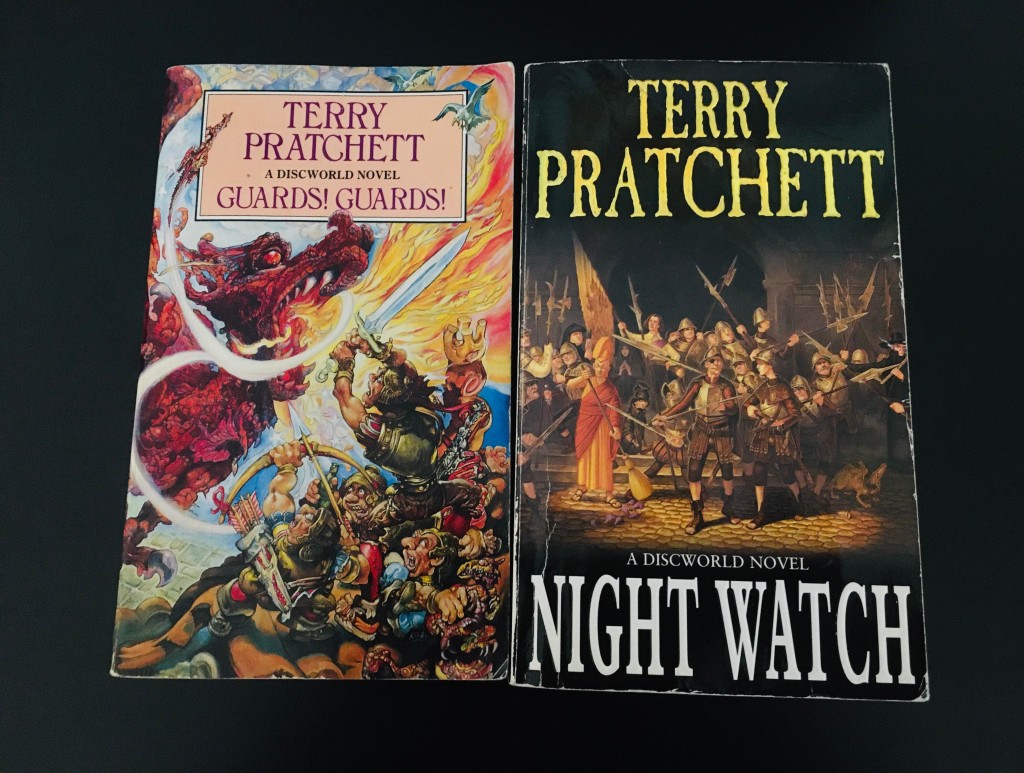

Mon mentioned they wanted to read more by Terry Pratchett, but we’ve agreed I get to read these first before I pass them on! Having loved Mort, Small Gods, and The Wyrd Sisters, I can’t wait to see more of this fantastical world.

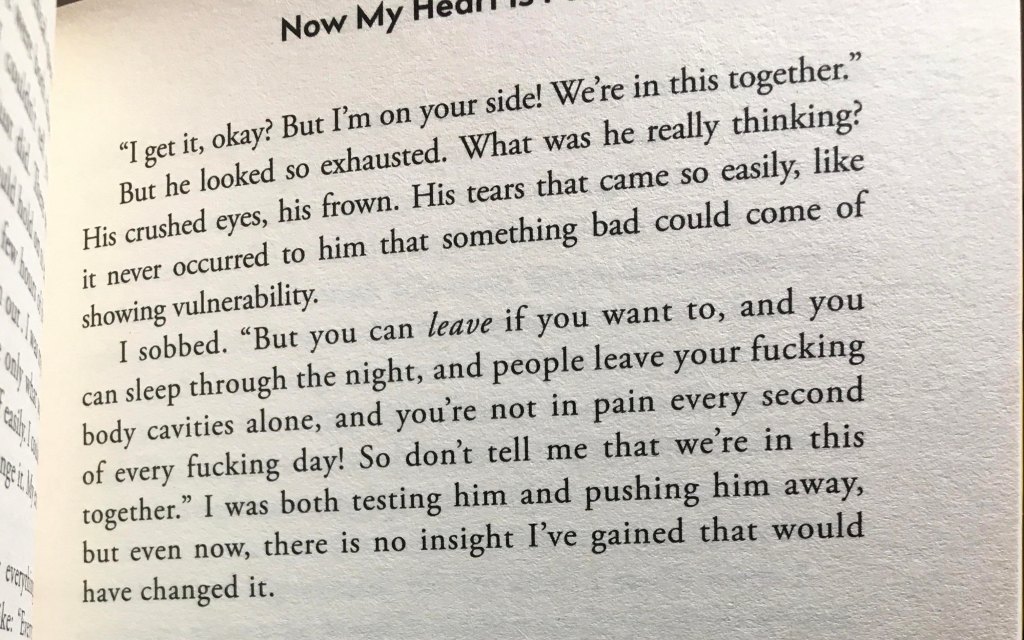

‘A is for Apple. A bad apple.

Jack has spent most of his life in juvenile institutions; he’s about to be released with a new name, new job, and a new life. At 24, he is utterly innocent of the world, yet guilty of a monstrous childhood crime.

To his new friends, he is a good guy with occasional flashes of unexpected violence. To his girlfriend, he is strangely naive and unreachable. To his case worker, he’s a victim of the system and of media-driven hysteria.

And to himself, Jack is on permanent trial: he struggles to start from scratch, forget the past, become someone else.

At a time when the privacy of the individual is under threat from all sides, BOY A raises fundamental questions about the morality of the media.’

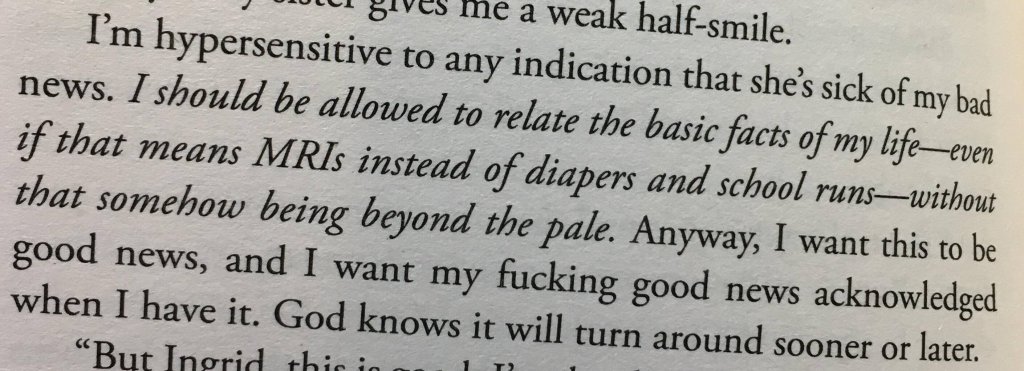

‘Few individuals have written about the evil forces of Hitler’s Germany with the immediacy and urgency of Gitta Sereny. She first encountered the Nazis in 1934 at age eleven when she witnessed a Nuremberg rally, and in 1940 she was in Paris when the Blitzkrieg overran the Allied armies. In 1942, warned of impending arrest for having hidden British pilots, she fled across the Pyrenees.

In The Healing Wound Sereny presents a vital historical account of Germany in the twentieth century, exploring the guilt which is in many ways the legacy of Nazism. She argues that despite the remarkable achievements of Germany since 1945, the awareness of the horrors committed in their name remains in the minds of Germans to this day — an open wound of historical culpability. The Healing Wound combines political statement with the haunting personal memories of one of the twentieth century’s most relentless witnesses.’

‘1910, Edinburgh. Jessie, the devil’s daughter, arrives on the doorstep of an imposing tenement building and knocks on a freshly painted wooden door. She has been sent by her father to bear a child for a wealthy couple, but, when things go wrong, she places a curse on the building and all who live there – and it lasts a century.

Caught in the crossfire are the residents of 10 Luckenbooth Close, and they all have their own stories to tell. While the world outside is changing, inside, the curse creeps up all nine floors and through each door. Soon, the building’s longest kept secret – the truth of what happened to Jessie – will finally be heard.’

‘Russia wakes from a long sleep and marches to St Petersburg to claim her birthright. Her awakening will mark the end for the Romanovs, and the dawn of a new era that changed the world. Arthur Ransome, a journalist and writer, was part of it all. He left his family in England and fell in love with Russia and a Russian woman. This is his story.’

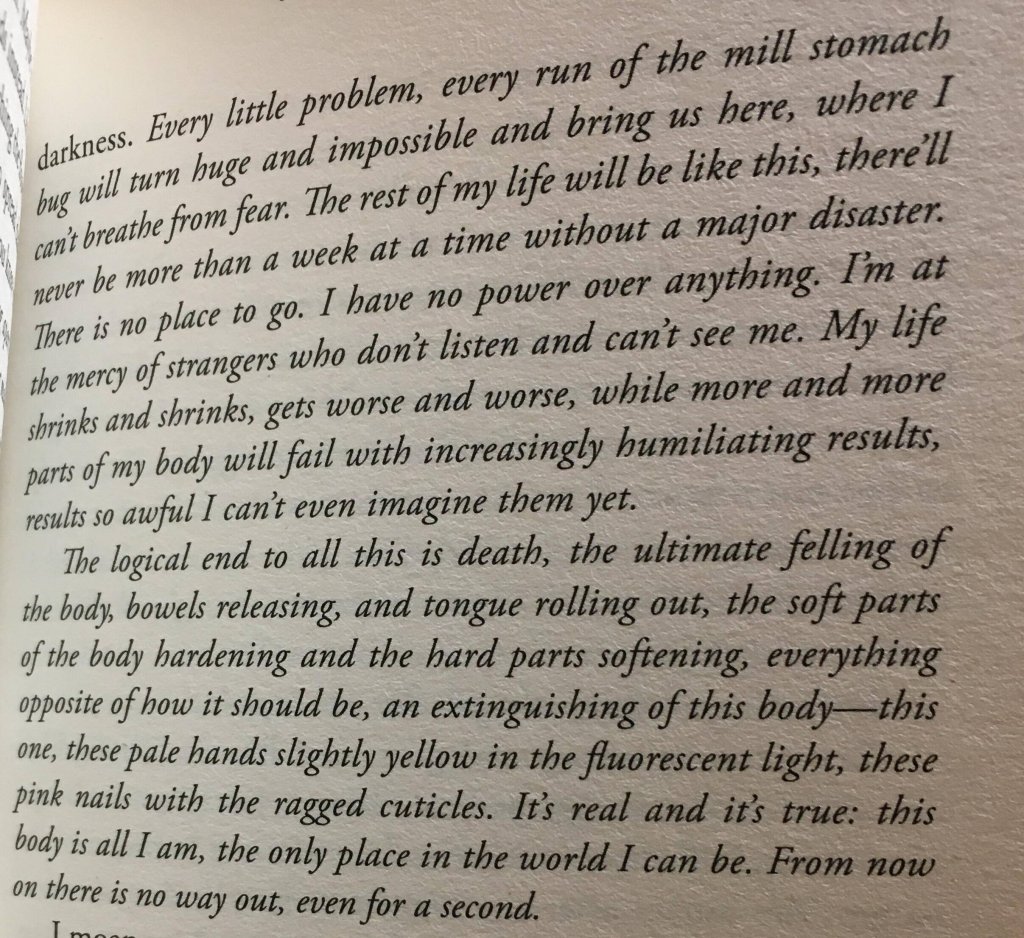

‘Set in Moscow in the 60s, written in an ironic style, this story combines realism with grotesque fantasy. Moscow radios announces an official “Day of Public Murder”, which permits any citizen to murder any other citizen. Yuli Daniel uses this to satirize hack literature, Soviet broadcasting, political naivety, racism, anti-semitism and the Soviet intellectual class.

Because of his activity publishing satire abroad, Daniel was convicted to five years in the Gulag. He was the first writer to plea innocent in a process of the kind, with fellow writer Synovsky, and the Daniel-Synovsky trial is considered the end of the Khrushschev thaw.’

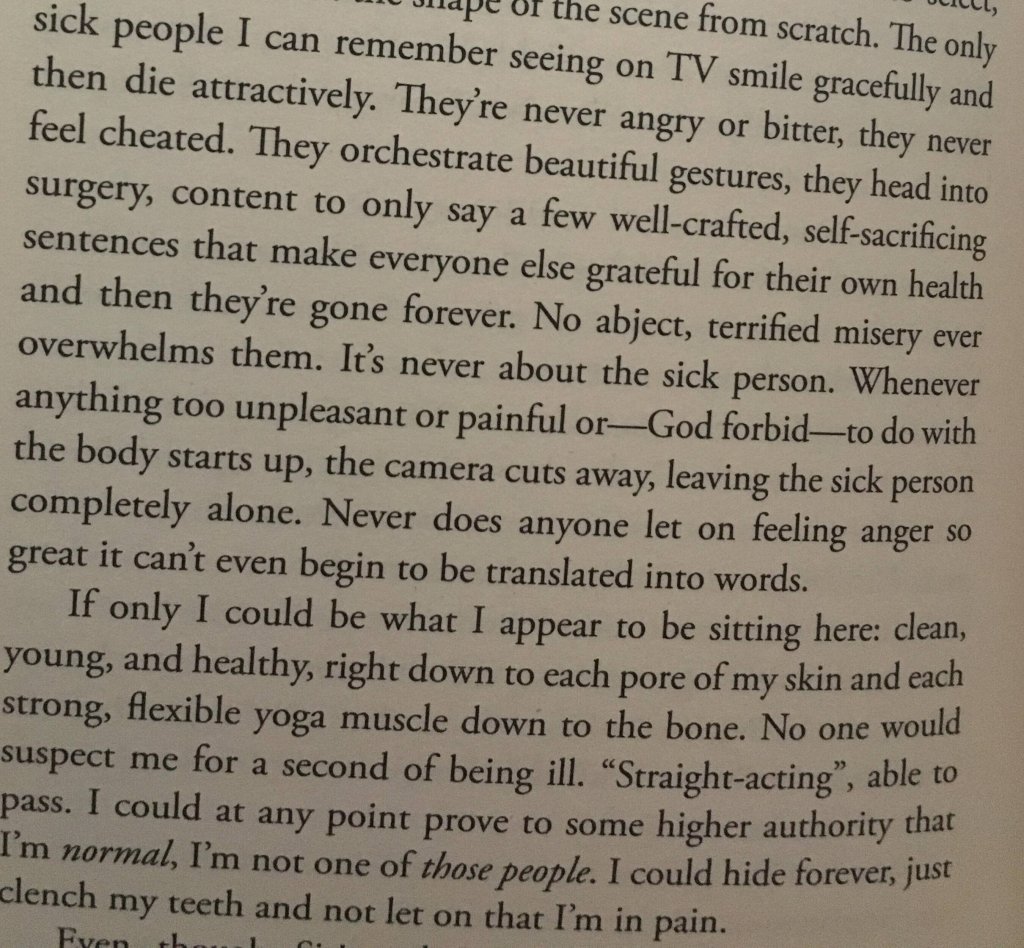

‘The story of a murder, a miscarriage of justice, and a man too innocent for his times . . .

Mahmood Mattan is a fixture in Cardiff’s Tiger Bay, 1952, which bustles with Somali and West Indian sailors, Maltese businessmen and Jewish families. He is a father, chancer, petty criminal. He is a smooth-talker with rakish charm and an eye for a good game. He is many things, but he is not a murderer.

So when a shopkeeper is brutally killed and all eyes fall on him, Mahmood isn’t too worried. Since his Welsh wife Laura kicked him out for racking up debts he has wandered the streets more often, and there are witnesses who allegedly saw him enter the shop that night. But Mahmood has escaped worse scrapes, and he is innocent in this country where justice is served. Love lends him immunity too: the fierce love of Laura, who forgives his gambling in a heartbeat, and his children. It is only in the run-up to the trial, as the prospect of returning home dwindles, that it will dawn on Mahmood that he is in a fight for his life – against conspiracy, prejudice and cruelty – and that the truth may not be enough to save him.’

***

I started reading Boy A yesterday, and I’m hooked so, if you’ll excuse me, I’m going to get back to it… If you get a chance to visit the Book Sale in Edinburgh, I’d highly recommend it. Thousands of books and all the money going to a good cause? Totally worth the trip.